EPISODE 3

A Deadly Reversal

By Sara Ganim

August 16, 2020

Tags: {!{wpv-post-taxonomy type=’post_tag’}!}

Runtime: 00:33:30

Below is a transcript of episode 3. We encourage you to listen to the episode. It was written to be heard, not to be read.

Sara Ganim narration: In 1977, professors at one of the largest public universities in the country started complaining that parts of the ceiling in their offices and classrooms were flaking off and falling. The university conducted a study, widespread testing in more than 100 buildings to find out; what is this stuff? Is it dangerous? It turns out, it most certainly is.

Mike Robb: That ceiling material was asbestos.

Sara Ganim narration: The university starts to remove it and simultaneously it sues the asbestos manufacturer, Johns Manville for $8.5 million dollars to clean it up.

Barry Castleman: The U.S. Justice Department had recommended that the owners of school buildings in particular should do just that, that they should file suit against the companies that had sold the asbestos material and get some financial help in getting it properly removed.

Mike Robb: It’s hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of schools. They wanted somebody else to pay for it

Sara Ganim narration: Facing so much litigation, sent Johns Manville and other asbestos manufacturers into bankruptcy.

Mike Robb: It turns out that that company only ended up paying a small fraction of that, less than $500,000.

Barry Castleman: They were paying, you know, nickels on the dollar to settle. Johns Manville created far more liability than its assets could ever pay.

Sara Ganim narration: And so, the university is left on the hook for a pretty big cleanup bill and when officials realize this.

Mike Robb: They do this about face. They changed their policy to going from removing as much as possible to removing as little as possible. Out of one side of their mouth they’re trying to get money to get rid of it because it’s so dangerous, but then when they realize they’re not going to get paid they just shut everything down.

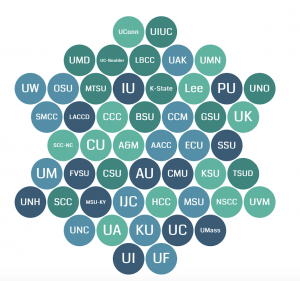

Sara Ganim narration: Our analysis of asbestos settlements and current records show that this was the case for dozens of universities across the United States.

Barry Castleman: One of the things that may have entered into it was this huge public

relations outreach that was done by a group calling itself the Safe Buildings Alliance.

Erik Olson: It’s basically a shell organization.

Linda Reinstien: They’re quite clever.

Erik Olson: According to documents that have come out the Safe Buildings Alliance was actually something that was formed at the behest of a PR firm to help companies that were using asbestos for buildings.

Barry Castleman: To basically convince the public at large that asbestos in buildings was really not a problem unless you disturbed it and that the best thing you could do was just leave everything in place.

Linda Reinstien: The industry used a lot of tactics like the big tobacco folks did, like “it’s really not a problem, don’t worry,”

Sara Ganim: Do you think that that’s true? Does the science support that argument?

Barry Castleman: No. I mean, this stuff is falling apart.

Mike Robb: Building materials don’t get stronger over time, right? They delaminate, they fall apart, they break apart. So, as time goes by, this material becomes more and more friable, more and more dangerous.

Sara Ganim: Do you think that these rulings had a ripple effect?

Mike Robb: It is a ripple effect. And when they find out that, “Hey, we’re not getting reimbursed for this by these property damage trusts so therefore, we’re not going to spend our money on it. We’re not going to remove it. We’re just going to keep an eye on it,” which is a lot cheaper.

Sara Ganim: So, today, how much asbestos remains in these buildings on college campuses?

Mike Robb: I guess nobody really knows that answer. But based upon what I’ve researched, I can only think that it’s thousands and thousands and thousands of square feet of asbestos-containing building materials. Based on what I’ve seen from my research on certain schools, it’s a staggering amount of asbestos in each and every school. But people don’t know how much because nobody says how much.

Sara Ganim narration: From the University of Florida’s Brechner Center for Freedom of Information, I’m Sara Ganim, and you’re listening to an episode of ‘Why Don’t We Know,’ the podcast that dives deep into data and comes out with real stories.

Mike Robb: Hi, this is Mike.

Sara Ganim: Hey Mike, this is Sara Ganim.

Mike Robb: Hey Sara.

Sara Ganim: So Mike let’s just start with a simple question. Tell me a little bit about yourself.

Mike Robb: My name is Michael Robb. I’m from Gibsonia, Pennsylvania. It’s just a suburb just North of Pittsburgh. I actually started off as an asbestos defense attorney. My dad, my father represented an asbestos mine in Canada for years. I actually worked with him for a few years. I always felt bad for the guys that got sick that breathe in the asbestos at these different locations. I always wanted to make the switch and represent the guy that was injured. I did that back in 2006. Ever since 2006, I’ve been representing steel mill workers, chemical plant workers, power plant workers, any type of labor or person who has worked with their hands for a living that developed lung cancer mesothelioma.

Sara Ganim: The type of people that are often the victims of these kinds of things.

Mike Robb: Exactly. They’re the ones that’s on everyone’s radar. They’re the guys that work there. My grandfather worked in the steel mill his whole life, right. That’s the guy that you think is going to call you every day and say, “Hey, I just got diagnosed with this. Will you represent me?” But as the years have gone on, we started seeing cases where people couldn’t tell where they were exposed because these people weren’t your typical steel mill worker or power plant worker. These people were educated. They did not work in heavy industry. Your first thought is, “Where could this person have been exposed to asbestos?” Had I never had a professor, a college professor, a PhD in organic chemistry. How does that guy get a PhD in organic chemistry, how does he get mesothelioma? It’s like, “Huh.” Then you start looking at where he was working in the classrooms that he’s in.

Sara Ganim: How many clients do you have right now related to universities?

Mike Robb: We have probably close to five now.

Sara Ganim narration: Asbestos is a mineral, mined out of the ground. It’s fire resistant, and it’s a great insulator, and that made it really appealing as a building material in the mid-20th century.

Mike Robb: Back in the day people would put asbestos in gloves, clothing, insulation for thermal properties. You would find it often in steel mills and power plants and then other industrial sites for various uses. But it also became popular for use in certain building products like floor tile, ceiling tile, ceiling sprays for acoustical purposes, and to stop the spread of fire, as well as thermal installations.

Sara Ganim: But asbestos was too good to be true, and health science quickly proved that it causes cancer, a specific kind of cancer in the lining of the lungs or stomach, called mesothelioma. The only known cause of mesothelioma is inhalation of asbestos fibers.

Mike Robb: When you look online and start doing some research, you see that, almost every college and university have older buildings and these older buildings during their construction in the ’40s, in the ’50s, in the 60s, in the ’70s contained asbestos containing building materials like floor tile, ceiling, tile, pipe insulation, HVAC duct work and ceiling sprays. You see that somebody has exposure inside the building that he’s working in, sitting behind a desk or teaching classes in because he’s standing on asbestos floor tiles or he’s standing under asbestos ceiling spray. So, it’s hard to avoid being exposed to asbestos when you’re in a building and you’re standing on it and you’re standing under it. I have a case against Pennsylvania State University for a gentleman named Peter Lebosky, who was a professor at Penn State from 1979 to 2002 when he was diagnosed with mesothelioma.

The first thing we did is just do some general research on Penn State University and other universities to see if there’s asbestos contamination there. I was shocked to learn that, and this is with respect to not just Penn State but many universities, that they have online environmental health and safety documents that say, “This is how we address radiation contamination. This is how we address water contamination from these labs, or this is how we address our asbestos problem.” Sorry, my dog is barking there.

Sara Ganim: Oh, that’s Okay. This is the age of working from home.

Mike Robb: Right. What I was saying, Sara, is that you go online and you look at these colleges and you should be able to see how they address their buildings that have asbestos in them. Some universities put a lot of information out there saying, “here’s the asbestos in this building in this room.” Others just say, “we have an asbestos control program, and we monitor it,” and that’s about it. So there’s either very little information or there’s some information, never a ton of information. But the question is, in 2020, why is there still asbestos in these buildings?

Sara Ganim: And why don’t we know about it?

Mike Robb: Right, right.

Sara Ganim: The short answer is that we don’t know because this is a true data desert. There is no federal law forcing universities to monitor air quality or share that information. There’s nothing even forcing them to report to the public where the asbestos is on campus. And the reason there is no regulation of asbestos is another legal case one that had a huge impact on the environment not just on campuses, but everywhere. It happened in 1989. The same year that Penn State abruptly changed its policy. The plaintiffs were manufacturers and the defendant, the United States Environmental Protection agency. Prior to that case, the asbestos industry in the United States was on its deathbed.

PBS News: Asbestos and its role with cancer banned from use in the United states

Sara Ganim narration: For more than a decade, anti-asbestos activism had been collecting up victories. In 1976, the clean air act classified asbestos as a pollutant and gave the EPA the power to regulate it. Then in 1980, the occupational safety and health administration, better known as OSHA, announced that no level of exposure is safe. In 1986, the EPA placed restrictions on its use in schools. Environmental consultant and asbestos historian Barry Castleman told me.

Barry Castleman: Cases of mesothelioma were starting to be reported in school teachers with no other known history of exposure to asbestos except that they work in buildings that had asbestos materials in them.

Sara Ganim: And then in the summer of 1989, the EPA issued ‘the asbestos ban and phase-out rule,’ which would have stopped all manufacturing and importing of asbestos. The environmental activists were not just making strides, they had crossed the finish line and were celebrating. But the victory was short-lived.

CSPAN: First we want to indicate that Epa’s proposal to ban asbestos lacks scientific credibility

Barry Castleman: Back in those days, there was what was called the race to the courthouse, when the government published a regulation and industry wanted to challenge that regulation, they would pick the most reactionary of the circuit courts that they could possibly find of the 12 U.S. circuit courts and file their challenge to the EPA rules there.

Sara Ganim narration: The asbestos industry did just that

CSPAN: “The scientific basis of the proposal was very, seriously flawed

Sara Ganim narration: They sued the EPA, arguing in court that banning asbestos would lead to job loss and economic crisis. Death by regulation, they called it.

CSPAN: “EPA clearly overstates its case concerning the risk to the general population of the United States”

Sara Ganim narration: The argument prevailed.

Barry Catsleman: It was some cracker court in New Orleans had basically decided that the EPA rules would have to be overturned.

Sara Ganim narration: Just two years after it was enacted, the ban was overturned by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in Louisiana, claiming the EPA failed to prove that a ban was the least burdensome alternative to regulating asbestos.The EPA never tried again. And because of that, the United States is one of the few industrialized nations in the world without an asbestos ban. It put the us back in the company of countries like Syria, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and China.

Linda Reinstien: If I go to Whole Foods, I can make a consumer choice to buy something organic, something that’s natural or something that’s just less expensive, but I have that option. But when it comes to contaminated asbestos products, because there’s no ban, I don’t know where there is asbestos.

Sara Ganim narration: All of the experts I talked to for this story, they all mentioned the same thing, when it comes to contaminants in our environment, asbestos is particularly frustrating because most people don’t know that it is no longer banned.

Barry Castleman: The ban got more publicity than its being overturned in court two years later.

Erik Olson: I think most people would be absolutely flabbergasted to hear that it’s perfectly legal to use asbestos in many commercial products.

Sara Ganim narration: That’s Erik Olson, the senior director for health at the Natural Resource Defense Council.

Erik Olson: There’s still a lot of uses that can cause people to be exposed in a way that’s really dangerous.

Linda Reinstien: It is the perfect crime. I live in L.A. and you couldn’t write the script for asbestos.

Sara Ganim narration: And this is Linda Reinstein, president and co-founder of the Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization.

Linda Reinstein: It’s been known for over 100 years that asbestos exposure could cause disease, suffering and deaths. And why don’t we know about this? I think nine out of 10 Americans think asbestos has been banned. So it’s been brilliant.

Sara Ganim narration: The only real, effective action that has stopped asbestos use in the last 40 years, are lawsuits. Lawsuits like the ones Mike Robb is filing.

Erik Olson: Frankly, it’s up to the trial lawyers to sue on behalf of people that have gotten mesothelioma cancer to force the industry to change practices. The industry is only worried about their wallets.

Sara Ganim narration: The 1986 law that placed restrictions on the use of asbestos in schools does still exist. However, it only applies to K-12 institutions, not to universities.

Mike Robb: Why do we not mandate that the colleges and universities that are getting federal funds, state funds. When you’re in 12th grade in high school the very next year you can go to a college campus and be totally exposed to asbestos. The question is how do you allow people to be exposed to a carcinogen and you just look the other way? It just dumbfounds me.

Sara Ganim narration: Some universities post what’s called an Environmental Health and Safety Report. We reviewed dozens of them and what we found is that those reports are varied and many won’t tell you very much. Of the 50 that we reviewed, only four schools say what buildings contain asbestos. Some mentioned that more than 90 percent of buildings contain it but won’t tell you which ones. None of them posted air quality test results for the public to see. And there isn’t a do-it-yourself way of figuring it out on your own.

Linda Reinstien: Because you can’t see it touch it, taste it, smell it, the average person can’t identify asbestos, or manage the risk.

Sara Ganim narration: The result is that we are held hostage by the claims of universities. We have to trust them when they say they are taking care of it with no system of checks and balances. But when you drill down into some of the documents that are posted online it’s not too comforting. Here are some examples from our research. At several universities, we found documents that advise individual departments to purchase floor mats to be placed underneath chairs that would prevent them from scratching asbestos tiles. Some universities warn that items like adhesives behind whiteboards and bathroom tile grout are not sampled but could contain asbestos. One major state school had just a single line buried in a 25-page document posted online warning that the ceiling surface does “contain asbestos”. The only information provided was to avoid contact. And at the University of Montana, there were calls for widespread testing last year because asbestos was found in a building that housed a pre-school. But there are no recent test results for the rest of campus are posted online.

Mike Robb: It feels to me that these asbestos control programs are only established and put online to make people think that any asbestos that’s in this place is being controlled. But you don’t really have access to the data. You don’t have access to the testing. You don’t even know if they’ve done any testing or performed any testing. You don’t know if there’s air sampling. You don’t know how much asbestos is in what room. And if it is in a room, is it in the floors, is in the ceiling, is it coming through the air ducts? You don’t really know. So, I think generally speaking, from what I’ve seen in my experience, it doesn’t appear that the information that people need to know or see is being disseminated by any university.

Sara Ganim narration: It gives asbestos control program a whole new meaning, doesn’t it?

Mike Robb: To keep it under wraps and under the guide of, “Oh, we have an asbestos control program.” You know, what are you controlling? Are you controlling the asbestos, the hazard? Or are you just trying to keep it quiet so people don’t get up in arms about it. They’re limiting the information and just hoping or making you feel like everything’s under control, right. That’s worse, I think, than doing nothing.

Sara Ganim narration: In the case of Penn State professor, Peter Lebosky, the university was forced turned over 20 thousand pages of documents, decades of internal memos and reports detailing Penn State university’s knowledge of the problem and its failure to clean it up. The timeline goes all the way back to the 70’s, when Penn State sued the asbestos manufacturer and didn’t get the $8.5 million dollars it needed to get rid of all the asbestos. At the time, the university admitted that nearly 450 buildings have asbestos in them.

Penn State’s industrial hygienist, the person in charge of identifying workplace hazards is a woman named Maurine Claver, and she gives an interview to the campus newspaper, saying, “the asbestos is everywhere.” Three days later, a memo went out to a number of officials, including Claver, stating the university “cannot afford” to remove asbestos as it had planned.

It says, quote, “in all future projects, our goal should be to minimize the removal of asbestos to only what is absolutely required. Obviously, this will help us a lot in the area of project budgets.” In the version the document that Penn State handed over for the lawsuit, those words are underlined in pen, and in the margins next to those markings there’s a hand-written note from Claver.

It says, “come on!!” with two exclamation points. Clearly Claver wasn’t buying it. And for the next 17 years, Robb says officials basically just sat on the problem. Documents show they didn’t warn students or professors, they didn’t even keep tabs on where the asbestos was until the early 2000s, when figuring out what buildings contained asbestos became a way to improve the look of their balance sheets.

Mike Robb: In 2006, Penn State goes and tests more of their buildings or the rest of their buildings, and they find that just over 500 of their buildings contain asbestos.

Sara Ganim: From a financial standpoint, what would it cost them to remove it.

Mike Robb: When you look at everything now, I think the documents, our math added up to around $35 million to remove all the asbestos.

Sara Ganim: The price increase is because they didn’t act on it and the market changed?

Mike Robb: Exactly. Every year it gets more and more expensive to remove asbestos. It requires a lot of permitting. You can’t just take asbestos and bury it anywhere, it has to go to a certified landfill. You have to have certain types of trucks that can remove it and carry it from point A to point B. It’s expensive and it’s a process, but it’s not impossible because companies do it all the time. You know that you have widespread asbestos contamination in your buildings, the longer you wait, you know that it’s going to cost more down the line.

Sara Ganim: When you say it’s really expensive to remove it, I mean, that’s relative, right? You’re talking about giant universities with pretty large budgets.

Mike Robb: It’s a great point. So these massive university systems that have billions of dollars, not only in annual revenue, or annual operating budgets, but they’re also worth billions. From my position, spending money that you have to make people safe is worth every penny when it comes to the safety of your faculty and your staff and your students, how much is their life worth?

Sara Ganim narration: We did some math. Penn State’s operating budget for 2020, it’s 6.8 billion dollars. Plus it has an endowment of $3.2 billion $800 million of which can be spent at the discretion of the board. If it costs $36 million to clean up this stuff that’s less than a half of one percent of the ten billion dollars the university states on tax documents. For the last ten years, each year, Mike Robb says Penn State spent more money on landscaping than it did to abate asbestos. Meanwhile, students studying about the hazard of asbestos in a class taught by an industrial hygienist are learning in a classroom building that still contains asbestos. And if you’re keeping track, it’s more than 40 years after they started looking for it.

Mike Robb: When you have billions of dollars available year after year, billions of dollars, you have a net worth of billions of dollars and you have endowments worth billions of dollars, why do you have asbestos in your buildings? It’s because you don’t give a shit, and you don’t want to spend the money to remove it. That’s why, period. Anybody that says anything different is wrong. I mean, why do you spend hundreds of millions of dollars for football practice arenas, and fields and things like that? Because you want to spend the money. Or you go out and you tell people, “Hey, we need money for this.” Well, you’ll never see one of these universities going around begging their alumni for, “Hey, we need money to remove the asbestos that we exposed you guys all to for the last you know, 100 years.” It’ll never happen.

Sara Ganim narration: In court Penn State argued that it has nothing to hide, that it turned over tens of thousands of pages of documents and attorneys for the university indicated they will fight the premise of the case. In response to our request for an interview, the university said it won’t comment on pending litigation.

Mike Robb: If you’re not going to talk about a problem or tell anybody about a problem, are you really going to sneak around and spend money to remove it behind the scenes when nobody knows, or are you just going to pretend like everything’s fine and hope that it doesn’t hurt anybody?

Sara Ganim narration: More documents obtained as part of the lawsuit show that Penn State found it would not be “economically feasible” to do air monitoring.

Mike Robb: So if you don’t do air monitoring, you don’t come in and actually sample the air and test the air and then figure out how many asbestos fibers are in the air per cubic centimeter, how do you know that it’s safe in those buildings? If you don’t look, which they don’t, then you don’t find, and that’s good for them. If you don’t want to tell everybody about all the hazardous asbestos, then the last thing you want to do is go in and start doing air sampling. Because if you find something that you don’t like and the numbers are too high or it’s dangerous, then it’s on their hands whether they’re going to report it or not.

Sara Ganim: They are not doing air sampling. It’s not that they’re keeping the information from the public, they’re really just not doing it. They don’t even know.

Mike Robb: Yea Exactly. But what about all the fiber fallout as a building vibrates or shakes, or naturally with air movements and kids slamming doors or walking on floors and they cause this vibration? Those ceilings shed, it’s called fiber fallout, and give off fibers, to which Penn State has reported that they feel it’s a very low level of fiber fallout and the exposures are very small, so basically don’t worry about it.

Sara Ganim: Have you guys been able to visit the office where your client worked?

Mike Robb: Yeah, we’ve been on a few site inspections there.

Sara Ganim: Were you able to do any air quality testing?

Mike Robb: No. We didn’t do any air testing. We were allowed to do bulk sampling where you test certain materials. We were able to test materials in the mechanical room of one of the buildings, which is where the HVAC systems are.

Sara Ganim: Can you tell me what you found?

Mike Robb: I can’t tell you the results, but I can tell you that our suspicions were correct and that there was asbestos present, not only in the actual building itself, but all also in the mechanical room where the HVAC units are.

Sara Ganim: That’s the room that draws the air that everyone breathes, because it goes from the HVAC system into the vents and then into the building rooms, right? That’s the air that everyone breathes.

Mike Robb: Exactly.

Sara Ganim: And you found asbestos in there?

Mike Robb: Yeah, we did. It’s our position that he was exposed every single minute of every single day that he worked inside of these buildings because he wasn’t holding his breath in there for 22 years when he worked there.

Sara Ganim narration: One of the many documents that this lawsuit has uncovered is a report that shows Penn State was aware that asbestos travels through the HVAC system and disperses the toxin throughout the building. Another document shows that when construction would begin officials in the office of the physical plant would warn maintenance workers about the dangers of asbestos. And in some cases, they did remove it if it was already part of a budgeted renovation project. But still, to this day, Penn State has no formal abestos awareness program.

Sara Ganim: This may be a really naive question, but if there is no law regulating it, how are you able to sue a university for someone’s death?

Mike Robb: Well, in most instance instances, you could file a claim for negligence, meaning, you’ve, you owed a duty to the person and you failed to protect that person by not protecting them from the asbestos, by not telling them about the asbestos and not providing a reasonably safe work environment. And that’s how we’re able to go after universities for these types of claims.

Sara Ganim narration: Legal cases like this are not common. We were only able to find a handful of others. And Robb says, its perhaps because the most challenging thing about taking on asbestos on college campuses is that unlike any other topic we’ll explore this season, the consequences are not immediate. Mesothelioma does not develop for 20 to 40 years after exposure to asbestos fibers. Imagine being diagnosed 40 years after college, and then trying to back track to show that you were exposed. Would you even remember what dorm you lived in? Where your classes were held?

Mike Robb: If you think about it, my grandfather was a steel mill worker for US Steel. Worked in the same department his whole life. He knows where he was. You and I are a little bit different, right. I went to undergrad, went to law school. You’re going to different rooms, different buildings. And if you’re not really thinking about, “is there hazard in here that could give me cancer at 20 or 30 or 40 years down the road?” These cases against the universities and colleges, they’re unique in that one, they’re not easy because you’ve got to do a lot of investigation. Every business, whether you’re a school or a corporation, they’re banking on the length of time. And the more I look at universities and colleges and their procedures and their methods about how they address asbestos, it feels like a very common theme, where it’s, they kind of know where it is, it’s low key, they don’t tell people about it, and then they just sit back and hope that it doesn’t come back to haunt them in a form of litigation down the road.

Sara Ganim narration: And even though he’s seeing more cases pop up.

Mike Robb: I think it’s just the tip of the iceberg, these types of cases. If I stopped you on the street and said, “Hey Sara, there’s all kind of asbestos in that old steel mill that’s closed down over there,” you’d be like, “Yeah. So…” It wouldn’t shock you. But if you stop people and say, “Hey where does your kid go to school? Oh yeah, there’s asbestos in that building.” They’d be like, “What? Why?” It would shock people.

Sara Ganim: And horrify them, I think.

Mike Robb: Yeah. It’s like, you’re so protective of your kids and you want them to do great and you want to give them the world and give them the best opportunity you can. And for someone to go to a college and sit in a classroom where there’s asbestos present and no one tells them, it baffles me that that’s how some of these institutions are treating their students, their faculty, their professors. For an institution that has like Penn state has a hospital, they have a teaching hospital, they train doctors how to treat people and diagnose people with mesothelioma and to treat them for it. But the same university and their undergraduate buildings potentially are exposing every single person that goes into certain buildings to asbestos, which causes those diseases. It’s so contradictory and so, in my mind, outlandish. It breaks my heart when people, “Oh, my daughter goes to Penn State,” and I say, “Oh, what classes? What building does she take classes?” “Oh, she goes here and here.” And I’m thinking, “Oh my gosh. If you only knew.” It’s sad. And it’s..

Sara Ganim: It’s really scary.

Mike Robb: Oh, it’s terrifying. You’re not thinking about your 18-year-old taking a poli-sci class at Penn State or Pitt or wherever and they’re sitting right underneath an asbestos-coated ceiling, you know. It’s just not on anyone’s radar and I’m hoping that I could help change that.

Sara Ganim narration: Next time.

News 8 report: : The Irvine freshman was found unresponsive.

WWLTV: An 18 year old student pronounced dead.

Sara Ganim narration: On “Why Don’t We Know.”

Jessica Curbelo: Do you feel like students generally knew what happened to Alex?

Alex Beletsis Friend: General population? No

Sara Ganim narration: One of the most frustrating and persistent stories in higher education.

Daphne Beletsis: We’re just willing to lose young people every year for what?

Doug Fierberg: These are public institutions that have a serious health problem on their campus.

Sara Ganim narration: Hazing deaths and why we can’t seem to stop them

Walter Kimbrough: People don’t want to create that kind of record because that kind of record easily available would be used against an institution in a lawsuit.

Sara Ganim narration: This episode was written, reported and produced by me, Sara Ganim.

The associate producer is Tori Whidden.

In addition, Adriana Merino and Chastity Maynard filed public records requests for this episode.

This episode was edited by Luke Barrientos

Music for this episode was composed by Daniel Townsend.

Audio mixing was done by Luke Barrientos

The executive producer is Frank LoMonte.

‘Why Don’t We Know’ is a production of the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida.

A special thanks to the Hearst family foundation for proving the grant money that supported this reporting.

For more information about this episode, visit www.whydontweknow.org

No regulation

Asbestos is a mineral, mined out of the ground, that’s fire-resistant and works as a great insulator.

That made it really appealing as a building material in the mid-20th century. But asbestos was too good to be true. And health science quickly proved that asbestos causes cancer — a specific kind of cancer in the lining of the lungs or stomach, called mesothelioma. In fact, the only known cause of mesothelioma is inhalation of asbestos fibers.

But the general public thinks of asbestos as something for steel mill workers to worry about — not college professors.

Even seasoned asbestos litigator Mike Robb was no exception. He was shocked in 2014, when a case came across his desk, of a 22-year veteran Penn State professor Peter Labosky, who died of mesothelioma.

“How does that guy, a Ph.D in organic chemistry, how does he get mesothelioma?” Robb asked. “Then you start looking at where he was working in the classrooms that he’s in.

“Almost every college and university have older buildings and these older buildings during their construction in the ’40s, in the ’50s, in the 60s, in the ’70s contained asbestos containing building materials like floor tile, ceiling, tile, pipe insulation, HVAC duct work and ceiling sprays,” Robb said. “So, it’s hard to avoid being exposed to asbestos when you’re in a building and you’re standing on it and you’re standing under it.”

In the 1980s, as the science around asbestos harm became clear, advocates successfully moved to ban it, but the ban was reversed after just two years by a federal court in the New Orleans-based Fifth Circuit. An EPA rule restricting use in K-12 schools does not apply at the college level.

The result is that there is nothing forcing universities to remove asbestos, monitor air quality in buildings that contain it, or share any information about where it is.

The only effective action that has stopped asbestos use in the last 40 years are lawsuits like the one Mike Robb is now filing against Penn State on behalf of the Labosky family.

The reversal

As part of his lawsuit, Robb forced Penn State to turn over 20,000 pages of documents, decades of internal memos and reports, detailing Penn State University’s knowledge of the problem, and it’s failure to clean it up.

The timeline goes all the way back to the 1970s, when Penn State sued the asbestos manufacturer and didn’t get the $8.5 million dollars it needed to get rid of all the asbestos.

Court documents show that back then, the university’s industrial hygienist — the person in charge of identifying workplace hazards — was a woman named Maurine Claver, and she gave an interview to the campus newspaper, saying, “the asbestos is everywhere.”

Three days later, a memo goes out to a number of officials, including Claver, stating the university “cannot afford” to remove asbestos as it had planned. It says, quote, “in all future projects, our goal should be to minimize the removal of asbestos to only what is absolutely required. Obviously, this will help us a lot in the area of project budgets.”

In the version of the document that Penn State handed over for the lawsuit, those words are underlined in pen, and in the margins next to those markings there’s a hand-written note from Claver. it says, “Come on!!”

Claver – who couldn’t be reached for comment – wasn’t buying the budget argument.

And for the next 17 years, Robb says officials basically just sat on the problem.

Court documents show they didn’t warn students or professors, they didn’t even keep tabs on where the asbestos was until the early 2000s, when figuring out what buildings contained asbestos became a way to improve the look of their balance sheets.

“In 2006, Penn State goes and tests more of their buildings or the rest of their buildings, and they find that just over 500 of their buildings contain asbestos,” Robb said.

Removing it now would cost an estimated $35 million, Robb says.

“These massive university systems that have billions of dollars, not only in annual revenue, or annual operating budgets, but they’re also worth billions,” Robb said. “From my position, spending money that you have to make people safe is worth every penny. When it comes to the safety of your faculty and your staff and your students, how much is their life worth?”

At Penn State, tax documents show a $6.8 billion budget, plus a $3.2 billion endowment, with $800 million that can be spent at the discretion of the board.

Yet, for the last ten years, Robb says Penn State has spent more money on landscaping than it did to abate asbestos.

Meanwhile, students studying about the hazard of asbestos, in a class taught by an industrial hygienist, are learning in a classroom building that still contains asbestos.

“I mean, why do you spend hundreds of millions of dollars for football practice arenas, and fields and things like that? Because you want to spend the money,” Robb said. “Or you go out and you tell people, “Hey, we need money for this.” Well, you’ll never see one of these universities going around begging their alumni for, “Hey, we need money to remove the asbestos that we exposed you guys all to for the last 100 years.” It’ll never happen.

In a court hearing in February, Penn State argued that it has nothing to hide — that it turned over tens of thousands of pages of documents — and attorneys for the university indicated they will fight the premise of the case.

Penn State declined to comment for this story, citing pending litigation.

More documents, obtained as part of the lawsuit, show that Penn State found it would not be “economically feasible” to do air monitoring, but Robb was able to do some testing in the building where Labosky worked for decades and he found asbestos present in the mechanical room where the HVAC system operates and draws air to circulate.

“It’s our position that he was exposed every single minute of every single day that he worked inside of these buildings because he wasn’t holding his breath in there for 22 years when he worked there,” Robb said.

Court documents show that Penn State is aware that asbestos travels through the HVAC system, yet to this day, Penn State has no formal awareness program.

‘It would shock people’

Legal cases like this are not common. We were able to find only a handful of others.

And Robb says that is perhaps because the most challenging thing about these cases is that the consequences are not immediate.

Mesothelioma does not develop for 20 to 40 years after exposure to asbestos fibers.

Imagine being diagnosed 40 years after college, and then trying to back track to show that you were exposed. Would you even remember what dorm you lived in? Where your classes were held?

“I think every business, whether you’re a school or a corporation, they’re banking on the length of time,” Robb said. “And the more I look at universities and colleges and their procedures and their methods about how they address asbestos, it feels like a very common theme. … They don’t tell people about it, and then they just sit back and hope that it doesn’t come back to haunt them in a form of litigation down the road.”

And even though he’s seeing more cases, “I think it’s just the tip of the iceberg,” he said.

“If I stopped you on the street and said, ‘… there’s all kinds of asbestos in that old steel mill that’s closed down over there,’ you’d be like, ‘Yeah, so…’ It wouldn’t shock you,” Robb said. “But if you stop people and say, ‘Hey where does your kid go to school? Oh yeah, there’s asbestos in that building.’ They’d be like, ‘What? Why?’ It would shock people.”

Additional reporting was done by Tori Whidden and Adriana Merino.